📖 Table of Content:

Long before lions and tigers roamed the earth, saber-toothed cats ruled as North America’s apex predators. These powerful hunters, with their iconic long canine teeth, dominated the landscape for millions of years. Their fossils tell the story of diverse species that evolved different hunting strategies and physical adaptations to survive changing environments.

1. Smilodon fatalis

The most famous saber-toothed cat stalked the plains of North America during the Pleistocene epoch. Its massive 7-inch canines could tear through the toughest hides of prehistoric mammals.

Scientists believe Smilodon hunted in packs, taking down prey much larger than themselves like giant ground sloths and young mammoths. Their powerful forelimbs compensated for a relatively weak bite force.

Fossil evidence shows many individuals survived severe injuries, suggesting social groups cared for wounded members. The La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles have yielded over 2,000 Smilodon fatalis specimens, making it the best-studied saber-tooth.

2. Homotherium serum

Nicknamed the ‘scimitar cat’ for its shorter, serrated canines, Homotherium roamed North America from 5 million to 10,000 years ago. Unlike other saber-tooths, it had longer legs built for chasing prey across open grasslands.

Homotherium’s body resembled a mix between a lion and hyena, with sloping backs and powerful shoulders. Their teeth were designed for slicing rather than stabbing, allowing them to efficiently process meat.

Recent DNA studies of preserved specimens from the Yukon suggest these cats had excellent vision in low light. They likely specialized in hunting young mammoths and mastodons, as shown by tooth marks found on fossil bones.

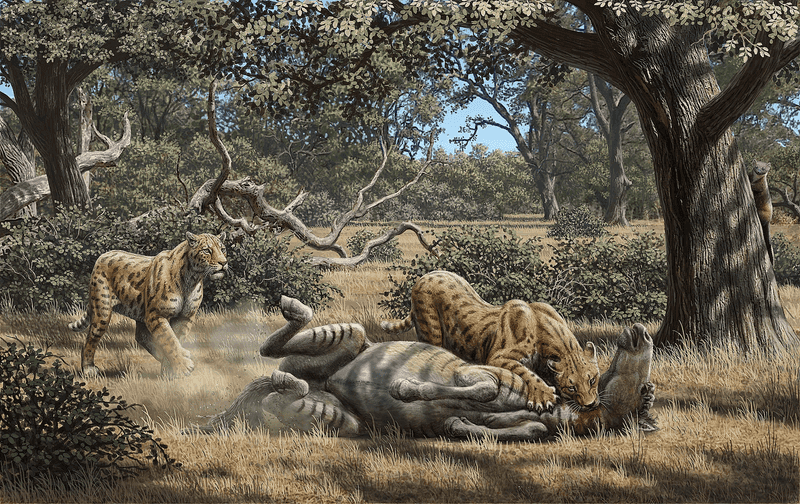

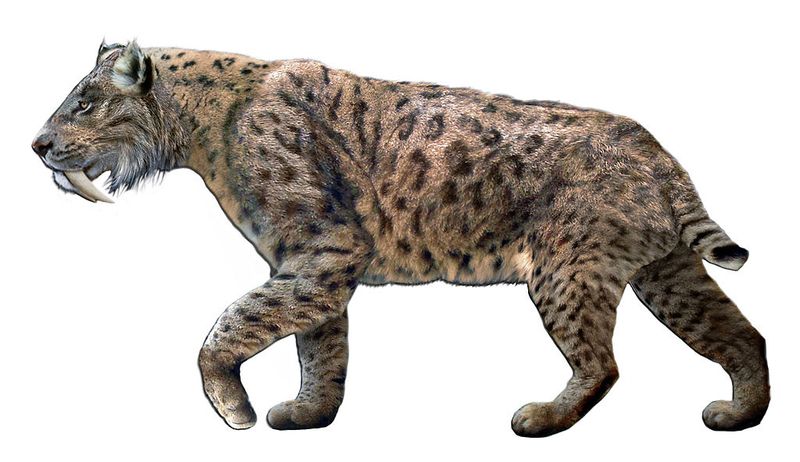

3. Megantereon hesperus

Megantereon arrived in North America around 4.5 million years ago. About the size of a jaguar, this cat possessed remarkably long upper canines relative to its body size and a flange on its lower jaw to protect these deadly weapons.

Bone studies reveal Megantereon had extremely developed neck muscles for a cat its size. These muscles helped deliver powerful downward stabbing motions with its fangs after ambushing prey from concealment.

Unlike modern big cats, Megantereon couldn’t roar due to differences in throat anatomy. They thrived in woodland environments where their compact, muscular bodies could navigate through dense vegetation to surprise victims.

4. Xenosmilus hodsonae

Discovered in Florida in the 1980s, Xenosmilus represents a unique evolutionary experiment. Rather than having just two elongated canines, this cat evolved serrated teeth throughout its entire jaw, creating a mouth full of steak knives.

Built like a bear with short, powerful limbs and a robust body, Xenosmilus likely ambushed prey rather than chasing it down. Its thick bones and heavy muscle attachments suggest tremendous strength.

Only two partial skeletons have ever been found, making it one of the rarest saber-toothed cats. These specimens were discovered alongside hundreds of peccary (prehistoric pig) bones, revealing its preferred prey.

5. Machairodus coloradensis

Among the earliest true saber-toothed cats in North America, Machairodus appeared around 10 million years ago. Roughly lion-sized, this predator had more modestly proportioned canines compared to later saber-tooths.

Fossil evidence shows Machairodus had a wide range across the continent during the Miocene epoch. Their anatomy suggests a combination of strength and agility, making them versatile hunters in the changing prehistoric landscapes.

Analysis of their limb bones indicates these cats could climb trees despite their large size. This ability would have given them an advantage in the mixed woodland environments of ancient Colorado and surrounding regions.

6. Dinobastis serus

Also called the ‘false saber-tooth,’ Dinobastis was among the last of its kind, surviving until approximately 10,000 years ago. Its teeth were shorter than those of Smilodon but still impressively elongated compared to modern cats.

Dinobastis had unusually long legs and was built for speed rather than ambush hunting. Remains found in Texas and Mexico suggest these cats preferred warmer southern habitats during the late Ice Age.

Intriguingly, some fossils have been found alongside human artifacts, raising the possibility that early humans encountered these predators. This timing coincides with the mass extinction of large mammals at the end of the Pleistocene.

7. Barbourofelis fricki

With the largest canines relative to skull size of any known predator, Barbourofelis was an imposing hunter. These massive teeth could reach nearly 10 inches in length, supported by an extremely robust jaw and skull.

Unlike true cats, Barbourofelis belonged to the nimravid family but developed saber-teeth through parallel evolution. Their front limbs were powerfully built with retractable claws, perfect for grappling large prey.

Fossilized remains show these predators had incredibly thick neck vertebrae to support the powerful muscles needed to drive their enormous fangs into prey. They roamed across Nebraska and surrounding regions about 9 million years ago, hunting early horses and camel ancestors.

8. Smilodon populator

Though primarily known from South America, fossil evidence suggests Smilodon populator occasionally ventured into southern North America. As the largest species of Smilodon, these massive predators could weigh up to 900 pounds—considerably larger than modern tigers.

Their enormous canines could grow to 11 inches, the longest of any saber-toothed cat. With such impressive weapons, they specialized in hunting the largest prey animals of their time, including giant ground sloths and prehistoric elephants.

Skeletal analysis reveals Smilodon populator had even more robust limbs than its relative Smilodon fatalis. This extraordinary strength allowed them to subdue struggling prey while delivering the fatal bite with their impressive canines.